Unstitching the homecoming story of the Bayeux Tapestry

With the news of the loan of the Bayeux Tapestry to the UK, I've been talking to the media about it, and I thought it might be fun to reflect on the loan and all that (sorry this isn't a Life Lesson)

The Bayeux Tapestry is coming home. Though we cannot say for sure, most experts who’ve looked at the epic embroidery1 of the Norman Conquest agree it was likely made in England, in Canterbury in fact, at some point shortly after the events it depicts2. So the news of the loan from its long-standing home in Bayeux, Normandy to the British Museum, London is a homecoming, of sorts.

Before I go on, if you’re coming here for Life Lessons from History content, I hope you don’t mind that this isn’t a Life Lesson style post (there’ll be another one of them next week), but rather this is a personal reflection on the big news story of the week, the impending loan of the Bayeux Tapestry to the UK, a topic in which I am quite invested. If you don’t want to hear about it, apologies, and stop reading now.

Anyway, back to the Tapestry.

Though there are still (valid) concerns about how this fragile 68m long piece of embroidered linen can be moved without risk, the loan is great news, I think, for anyone interested in history. It’s particularly exciting for me, because I co-wrote a book on the Tapestry, with Prof Michael Lewis, back before Covid hit. We put in the work on the assumption that a loan was imminent and there would be high interest in the Tapestry’s story. After all, in January 2018, President Macron and the then UK Prime Minister Theresa May said that the loan was going to happen. As it’s turned out, it took over seven years to sort it out.

I remember the first announcement well. It was a cold, dark January morning back in 2018 and I was stumbling around my kitchen getting a coffee well before dawn, trying to get the house sorted before my children got up and wrecked it. And then I got a phone call. A producer on Radio 4’s Today programme was on the line, wondering if I was willing to come on the show in an hour to talk about the big news. I had to admit, and I imagine this did not inspire confidence, that I was at something of a disadvantage. I had no idea what the big news was. So he caught me up: there was an Anglo-French summit going on, and an announcement was going to be made about the Bayeux Tapestry being loaned to the UK. That was the story. Ah.

As I said, this caught me slightly off-guard, so you might be wondering why the BBC’s flagship news would be coming to me for comment. Well, I’ve been working as a historical journalist and editor for BBC History Magazine and the HistoryExtra website and podcast for quite a few years, and as a consequence of that, I was in the contact books of a few producers as someone who could offer comment on historical matters. I had a particular interest in this topic, because ten years previously in 2008 (I told you I’ve been doing my job for a while), I’d written an article for the magazine about the Bayeux Tapestry. It was based on an academic conference held at the British Museum and the angle of my piece was to interrogate the case for the Tapestry being made in England.

The organiser of the conference, Michael Lewis, had made my job much easier by handily gathering together all the leading experts on the Tapestry in one place. So I was able to get some great quotes about the various arguments for and against the English manufacture of the embroidery. You can still read the piece on the HistoryExtra site if you like, though it is behind a paywall (sorry, we’ve got to make money from our content somehow).

Given that they were in broad agreement that the Tapestry was made in England, at the end of that article, I enquired of these experts whether they thought that we should ask for it back. There was certainly no consensus from them on that point, though Michael Lewis was very much in favour of the idea of it being displayed in the UK.

Rolling forward to that January morning of 2018, I imagine that an internet search had brought up that article on the HistoryExtra website, and alerted the Radio 4 producer to my interest in the Tapestry, and thus I got the call. A few minutes later I was on the radio, slightly surprisingly finding myself in a three-way discussion about the Tapestry and the politics of the loan with the presenter and the Conservative MP Tom Tugenhadt.

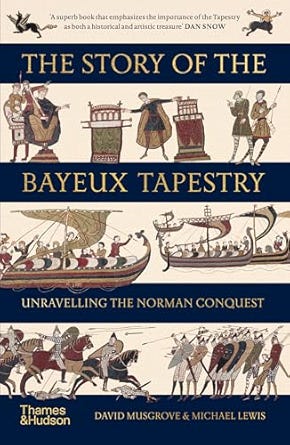

With the excitement of the offer of the loan in the air, I put my head together with Michael Lewis and we spent much of 2018 and 2019 researching and writing our book The Story of the Bayeux Tapestry: unravelling the Norman Conquest, which was published by Thames and Hudson in 2021. If you want to know the ins and outs of what the Tapestry is all about, obviously I’d heartily recommend reading it (don’t take my word for it, the Times Literary Supplement said it is ‘Beautifully illustrated and meticulously researched’).

Disappointingly, nothing much then happened by way of the loan after that. In July 2018, then UK Culture Secretary Matt Hancock had signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with Françoise Nyssen, the French Culture Minister, to begin working through the details. According to Lord Parkinson, the Heritage Minister from 2021 to 2024 under the last Conservative administration, who I chatted to last week: “The MOU was helping bring the political, the museum, the official levels, all together and trying to iron all of that out. But it was clearly difficult on the French side and the momentum stalled a little bit”.

A key part of the agreement involved the creation of a scientific committee to assess the condition of the tapestry and the feasibility of moving it. “They were understandably concerned about moving it and making sure that it was in the right condition,” said Lord Parkinson. “So there was a lot of work that had to be done, but also a lot of hurdles that started to emerge.”

The initial expectation was that the loan and exhibition would take place in 2022. That aligned with a proposed redevelopment of the museum in Bayeux, and a plan to have that newly revamped home for the Tapestry ready for the flood of visitors expected to northern France for the 2024 Paris Olympics.

The museum’s redevelopment project took longer to get going than expected, and that condition report on the Tapestry (carried out in 2020) highlighted the pressing need for conservation and stabilisation work to be carried out. The following problems were enumerated:

24,204 stains

16,445 wrinkles

9,646 gaps in the cloth or the embroidery

30 non stabilised tears

That, coupled with the ebb and flow of Anglo-French relations, and probably the fact that minds were elsewhere with a global pandemic and then the threat of European continental war, meant that progress on the loan was not fast. Nonetheless, I didn’t give up on the idea that it might happen: there is a press officer at the Department of Culture, Media and Sport who probably uttered a weary sigh when my quarterly email landed in her inbox asking for an update: ‘nothing to report, I’ll let you know if there is’, was the consistent reply

Finally, however, the plans for the Tapestry museum to close for its redevelopment got the go-ahead. They were officially announced and the date set for September 2025 for the tapestry to go into storage while the works happened. The new museum will open in 2027, in time for the millennial commemorations of the birth of William the Conqueror – a big deal in Normandy. So the window of opportunity for the loan to happen was temptingly pushed ajar.

It was always unlikely that the Tapestry would be loaned at any point outside of the museum’s closure, but there is an interesting complexity to the negotiations because the Tapestry is not actually owned by the museum in Bayeux: it is the property of the French state, a situation that dates back to Napoleon (who incidentally had the Tapestry moved from Bayeux to Paris at the start of the 19th century as a political gesture to support his planned invasion of Britain at the time). This isn’t the first time that a loan has been close: previous deals were proposed and then ultimately dashed three times in the 20th century. In 1931, for an exhibition at the Royal Academy; in 1953, to celebrate Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation, and in 1966, for the 900th anniversary of the battle of Hastings (not in anticipation of the England mens' team's World Cup football triumph). None of these came to pass, faltering under concerns over damage to the Tapestry, financial wrangling, and one imagines, a failure of political will.

So, in the end, the decision in 2025 was one for the French government: the recent renewal of enthusiasm of the loan has surely been politically charged, resulting from the new rapprochement between the British and French governments. Though also, it seems, finally pushed over the line by the active support from King Charles III, apparently a passionate supporter of the project.

Unlike 2018, when I was very much rudely awakened to the idea of the Tapestry loan, I did have an inkling that things might happen in this July’s Anglo-French summit. HistoryExtra had been given an interview slot with the Prime Minister Keir Starmer in May this year, to hear his thoughts on the VE Day commemorations, and I asked our journalist to drop in a question at the end, just enquiring whether he knew anything about the Tapestry loan. "The Bayeux Tapestry is a unique treasure,” said the Prime Minister, “and a symbol of the deep ties between Britain and France. The conservation and protection of it is obviously crucial, and I know that the Department for Culture, Media and Sport continues to work closely with their counterparts in France on the planned loan."

That was the first time I’d heard anyone give any concrete hint that the talks were still ongoing. I figured that, given that the whole story of the Bayeux Tapestry loan – and frankly the story in the Bayeux Tapestry itself – is one of political gesturing and deal-making, if any announcement were to be made, the state visit of President Macron to the UK provided the ideal platform.

That said, it was far from certain that a deal would be done. President Macron outlined the obstacles to the loan, from the French side, in his speech at the British Museum last week: “I have to confess, we did our best not to be put in this situation to make the loan of the Bayeux Tapestry. And we found the best experts of the world to explain in perfect detail why it was impossible to make such a loan. And believe me, we found them, and believe me, we could have found them again.”

Lord Parkinson credits President Macron’s personal determination for seeing the process through. “I think this really has come from Emmanuel Macron himself. In the Royal Gallery address to parliament this week, he saw Theresa May was sitting in the second row, and he acknowledged that this is an idea that began when Theresa May was Prime Minister and it’s taken too long. So I think he’s aware that he made this very kind suggestion [of loaning the Tapestry]. He wanted to deliver on his promise, and this summit has allowed him to do that”.

Clearly, the deal for the Tapestry is entwined with the larger conversations about Anglo-French relations, and the UK government’s wider desire for a reset with the EU. On the French side, I do wonder how big a deal the Bayeux Tapestry aspect is in the story. Back in 2018, I interviewed the Bayeux Tapestry Museum chief curator Antoine Verney. He pointed out that the tapestry means something quite different to French visitors (25 per cent of the footfall) who come to view the UNESCO-inscribed artefact. The British, he told me, tend to view the tapestry as a monument that marks the end of a period, while the French consider it more as the start of a story of Anglo-Norman expansion. He also sees a very different level of knowledge about the Norman Conquest across the Channel: for the British, the one date everyone knows is 1066; for the French, it is 1789. “A lot of French people think that Hastings is actually in Normandy,” he noted, “and that the battle took place in the Hundred Years’ War rather than the 11th century”.

Whatever the level of interest on the French side of the Channel, certainly in Britain, this is a hot topic. Immediately the news broke, I started getting calls from journalists to come on radio and TV programmes, and comment for papers on the subject. I was probably at the top of their contact books because I’d done a round of interviews just a few months ago when another Bayeux Tapestry story I’d been working on – the vexed question of how many penises it contains – hit the headlines.

It is always interesting to try to explain a historical story to a non-historical news outlet. I do a lot of interviews myself with historians for the HistoryExtra podcast (including, incidentally, a five-part series on the Tapestry, where I talked to a raft of experts in 2021, and just yesterday, a special bonus episode in the light of the loan news, where I talked to myself about the Tapestry), but there we are speaking to a historically enthusiastic audience and we have half an hour, or more, to explore a subject. When you go on a radio interview, you’ve got at best five minutes, likely far less than that3. Generally I find, your slot gets squeezed as you get closer to being on air because some other more consequential news story has broken. But the Bayeux Tapestry loan is a big story so I got a fair bit of time to talk. Here’s a run-down of the five questions that the people who interviewed me seemed most keen to address.

Was it really English? (ie was it made in England - the answer being probably yes, and that obviously plays to questions of national sentiment)

What actually is it all about? (hard to condense into a sentence, but basically the run-up to the Battle of Hastings and the battle itself, a two-person narrative throw-down between Harold II and William)

Why does it matter/why do we still care about a thousand-year old bit of cloth? (because it’s the visual powerhouse of the Middle Ages and it tells the story of the seminal event in English history)

Is it really just a money-saving exercise on the part of the the French so they don’t have to pay for the Tapestry’s storage while the museum is being redeveloped? (seems like a lot of trouble to go to if that is the case, so an unconvincing argument in my view)

Does it really have lots of penises in it? (yes, it does – 93 or 94 depending on your count. Sorry for making that a national conversation point).

What’s next for the story then? Well, we await details of what is actually going to happen and how. There is already some conservation work that has happened in Bayeux and that will continue. According to the Bayeux Tapestry website, this commenced in January 2025, “with the meticulous dusting of the linen canvas and the removal of its technical backing, a fleece affixed in 1983, which, although protecting the work on its back, stiffened and weighed it down. These upstream interventions will facilitate the extraction of the work from its display case when the museum’s renovation work begins in the fall of 2025”.

The Bayeux museum team have also been doing trial runs of how they are going to move it from its current display case (which they had to do whatever, because it needs to be shifted into storage out of the room). The plan, as I understand it, is to extend the railing system that it’s presently hung on into a temporary portable railing set-up, so that it can be gently rolled off its vertical hanging. Then, I assume there will be more conservation and stabilisation work done in Bayeux (though maybe that will happen in Britain – that hasn’t been confirmed), and when it travels to the UK, it will be folded, crated, double-crated, and then moved by road and rail, through the Channel Tunnel, to the UK. I imagine there will be quite some security operation for that. Despite these preparations, there are still those who are very much unconvinced of the wisdom of moving the Tapestry.

The last time the Tapestry moved any distance was in the Second World War, under very different conditions. With Normandy occupied, it was removed from Bayeux to a nearby monastery for German academics to study it (in an effort to prove that the Normans who conquered England were, in reality Vikings, and, by extension, Germanic), thence to a chateau near Le Mans, and finally taken to Paris. From there, it would have been removed to Germany, were it not for the determined prevarication of officials at the Louvre, and the timely arrival of liberating Allied troops.

I imagine the British Museum curators will be busily gathering up artefacts that pertain to the story of the Norman Conquest, and will deliver a compelling, world-class, multi-dimensional exhibition. Maybe they will be able to showcase some of the illuminated manuscripts that are thought to have been used as stylistic templates, and content inspiration, for the Tapestry designers. The Old English Hexateuch would be one such manuscript. That will need the buy-in of the British Library for that, but as has been shown with the loan itself, where there’s a will, there’s a way.

Certainly, one of the hopes of the loan, and the exhibition, is that it will allow researchers access to the Tapestry in ways that haven’t been possible of late. I’ve done a ring-around of experts to see what sort of projects they’d love to see happen. Look out for the next issue of BBC History Magazine for the full round-up, but as a taster, Professor Richard Gameson, noted historian of the book at Durham University, mentioned the idea of trying to directly compare those Old English illuminated manuscripts with the embroidery to see how far the Tapestry truly draws on them. Until now, such comparisons have been done at a remove.

Meanwhile, Manchester Metropolitan University’s Dr Alexandra Makin, an authority on Anglo-Saxon embroidery, would love us to be able to get really up close with the stitching to see what more we can learn from a very detailed examination of the work, most fruitfully probably looking at the rear of the linen panels. Maybe even there are scientific tests that could be carried out to examine where the flax for the linen was grown, or where the sheep from whom the wool was sheared were grazed, or where the material for the dyes was obtained. Obviously any such tests would have to be made with the utmost care, but the battery of scientific techniques at our disposal now are so far advanced from what was on offer when the Tapestry was last readily available for study, in 1982-83, that there must surely be much that could be done. And then there’s AI - there will be ways that artificial intelligence could be directed towards comparing, collating, referencing what’s in the Tapestry - maybe it could be tasked with trying to establish the individual hands of the embroiderers who worked on the project.

These are exciting times in the year or so ahead. If this isn’t the biggest historical exhibition ever to hit these shores, I’ll eat my hat, and my Bayeux Tapestry tie and tote bag. Let me know what you think about the Tapestry loan, and what you’re excited about in the comments. Will you be first in the queue, with me, to see the exhibition?

If anyone is worried about me flipping indiscriminately between tapestry and embroidery, rest assured that I am fully aware that the Bayeux Tapestry is in fact an embroidery. Its composition is text and images stitched, with dyed woollen thread, onto a linen backing sheet. A tapestry is produced by weaving threads and creating image and cloth at the same time. I won’t trouble you here with why that we have the wrong name for it. Everyone knows it as the Bayeux Tapestry though, and I’m not about to start advocating for the Canterbury Embroidery because that just doesn’t have the vibe.

There are a lot of indications to suggest that it was most likely produced in England by English embroiderers. England at the time had a reputation for its embroidery. The Latin textual inscriptions above the story-boards use Old English letter forms, and stylistically the work has parallels in Anglo-Saxon illuminated manuscripts. Plus, some of the vignettes in the tapestry appear to be based on designs that we know were found in manuscripts held in the library of a monastery in Canterbury, so there are those who argue that it was actually made not just in England, but more precisely in Canterbury. On top of that, Bishop Odo of Bayeux, William’s half-brother, is generally seen as the person most likely to have been the driving force for having the Tapestry made. After the Conquest, he was made Earl of Kent, which covered Canterbury.

If you’re a writer or historian wondering about what happens if you get asked to do media work, let me share my experience.

You’ll be being asked on as an expert or someone with something to say on the subject, so obviously prep for the interview and think about what they might ask. And of course, clearly, the context of the media outlet you’re going on is worth thinking about. When I go on BBC Radio 5, I know they like a bit of a lighter side at times, and if you can tie things into sport in some way, they appreciate it. Not so much on Radio 4 I don’t think. On BBC local radio, it’s great fun because I find the presenters there are quite happy to wander off on surprising tangents, so be prepared to speak about pretty much anything if you end up on BBC Radio Cornwall or the like – and make sure you have some sort of anecdote pertinent to the region you’re talking to there. If you’re going on a commercial station, again, just think about where they might be coming from, if they have an obvious editorial slant.

I always ask if there is anything particular the interview might be framed around, but don’t be surprised if, when it comes to it, the conversation goes in a completely different direction. You’ll have to roll with it.

Media training I’ve done in the past suggested that you should make sure you have a clear line about what you want to say and say it, whether or not that attends to the question you’ve been asked. You hear that approach from politicians sometimes, and I don’t think that does the listener a service. Sure, if there’s something you want to get across, include it in your answer, but make sure you respond to the question too.

If you’re asked something that you do not know the answer to, I really don’t think there is any point blustering your way through. I’ve done that once and I regretted it because I just ended up waffling. Sounds rubbish. A better approach, I’d venture, is to pause, don’t panic, and say something like ‘honestly I don’t know the answer to that, but I do know this…’ and maybe then take your answer back to the point you want to talk about – that’s a more transparent and authentic way of doing it.

Crucial thing is to make sure you’re comfortable and relaxed for the conversation (and assume it is a conversation rather than interrogation, unless you’re coming in with a particularly controversial line that you know is going to be queried). Get yourself in a quiet room, assuming you’re not going into studio (that doesn’t happen so much these days), make sure your internet is good, close down all your wifi-sapping apps and your noisy alerts. Check if they want you on camera or not. And even if you’re told there’s no video, be ready for that not to be the case when it comes to it – tidy up, remove anything from your background you’re not comfortable with being subject to wider scrutiny. Try to get your lighting to be generous to your face, and don’t have a window blazing sunlight in behind you.

Have fun. It’s great to be able to share what you know.

You may be interested to hear about the Battle of Stamford Bridge tapestry, which a group of volunteers (including me) stitched in the style of the Bayeux Tapestry between 2015 and 2021. As you know, the battle of Stamford Bridge took place outside York on September 25, 1066 against the Scandinavian army led by Harald Hardrada, less than a month before the battle of Hastings.

Our website is here: https://stamfordbridgetapestry.org.uk/

and contains full colour photographs of each of the fifteen 1.5m long panels.

Lovely article, thank you. I’m very excited to see the tapestry in person. The penis question always fascinates me - I do wonder how many of them are a result of larking about by the women stitching it (because it would have been largely women, surely?). A group of women spending lots of time together can get quite mischievous - and I’m sure that was the case in 1066 as much as it is in 2025! ☺️